Yes, Ted Cruz IS Eligible To Serve As President

Hat/Tip to Greg Conterio at Western Free Press.

In doing so, we begin to evaluate those among us who may seek to hold the highest office in our land. There are many potential contenders out there, on both sides of the aisle, so to speak. We have of course Hillary on the Democratic side, along with Elizabeth Warren, Andrew Cuomo and even Michael Bloomberg.

Along Republican lines there are a lot of names that might throw their hat into the ring; Sarah Palin, Rand Paul, Chris Christie, Paul Ryan, Jeb Bush, Mitt Romney (despite his protestations to the contrary), Dr. Ben Carson, Marco Rubio, Allen West and Ted Cruz.

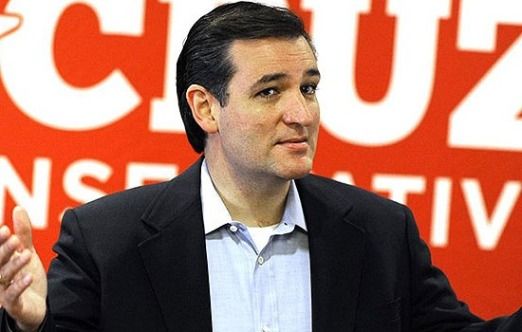

Now among that list of folks, one name draws a specific argument – an argument that isn’t limited to one side of the aisle or the other. It is the possibility that Ted Cruz may not even be eligible to run. So in that vein, I’ve decided to reprint in its entirety, a piece that ran in the Western Free Press by Greg Conterio. In his piece he breaks down the subject of Ted Cruz’s eligibility, once and for all.

~~~~~~~~~

Yes, Ted Cruz IS eligible to serve as president

by Greg Conterio

As the American political right begins to set its sights on the 2016

presidential election, a bit of a kerfuffle has persisted over the eligibility

of Ted Cruz, should he decide to seek the Republican nomination. Most

confusing for some may be the persistent voices on the right who insist

Cruz is ineligible. While I find it incredibly bizarre that people who

are staunchly on the right would be spending so much energy trying to

disqualify one of strongest, most conservative political leaders our

side can field, I can assure you that however well-intentioned their

views may be, they are mistaken in their understanding of Cruz’s eligibility.Let us see if we can walk through this, one piece at a time.

First, let’s take a quick look at the law itself. The qualifications for serving as president are laid out in the Constitution, which among other things says:

“No person except a natural born citizen, or a citizen of the United States, at the time of the adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the office of President…”So, natural born citizen—check. This is the part for which it is claimed Cruz doesn’t qualify, but what exactly is a “natural born citizen”? Despite the great amount of debate, there truly is one and only one legally controlling authority, and that is U.S. Code law and, of course, its interpretation.

This matter is, or ought to be, largely outside debate. The Constitution defined our government, and the boundaries and constraints under which it would operate. However, the Founders understood that a body of code law would have to be created within the Constitution’s framework, and they gave the power to create laws to Congress. The Constitution is a short, simple document, and rightly so. It is up to Congress to create laws that faithfully represent the intent of the Constitution.

In other words, the Framers didn’t spell out a definition for “natural born citizen” because it was deliberately left to Congress to determine. Indeed, a faithful interpretation of the Constitution—a document revered by us conservatives—must include recognition that this power was granted to Congress. The legal definition of a “natural born citizen,” a.k.a. a “citizen at birth,” can be found in section 1401, Subchapter III of the U.S. Code.

Now, let us look at how this applies to Ted Cruz, and see if we can’t put this question to bed.

Senator Cruz was born in Calgary, Alberta, which of course is in Canada. The senator’s father, Rafael Cruz, is from Cuba, and has quite an interesting story himself, but was not a citizen at the time of his son’s birth. His mother, Eleanor Elizabeth Wilson, however, was a citizen, having been born and raised in Delaware. Eleanor attended Rice university in Texas, where she also worked for Shell Oil Company as a programmer after graduating.

This brings us to subsection (d) of section 1401 of the previously mentioned U.S. Code, which in defining those who are legally citizens at birth, reads:

(d) a person born outside of the United States and its outlying possessions of parents one of whom is a citizen of the United States who has been physically present in the United States or one of its outlying possessions for a continuous period of one year prior to the birth of such person, and the other of whom is a national, but not a citizen of the United States; (emphasis mine)This is the aspects of the U.S. code which pertains to Senator Cruz.

a person born outside of the United States and its outlying possessions

Ted Cruz was born in Canada.

of parents one of whom is a citizen of the United States

His mother was a U.S. citizen, born in Delaware.

who has been physically present in the United States or one of its outlying possessions for a continuous period of one year prior to the birth of such person

His mother was born, raised, and lived in the United States. She was thus “physically present in the United States” for far more that the required “continuous period of one year prior to the birth of such person.”

and the other of whom is a national, but not a citizen of the United States

His father was a U.S. national, but not a citizen. He was married to Eleanor Elizabeth Wilson, a U.S. citizen, thus making him a national according to the law.

Ted Cruz fits all the requirements established in Section 1401, Subchapter III of U.S. Code for being a citizen.

There are a number of important things to understand here.

First, and most essential—the only controlling authority on this question is U.S. law. Skeptics have put forth the belief that 18th century common law or quotes from the Founders have authority over this question. They do not. While we revere both the wisdom of our predecessors (handed down through human institutions such as tradition and common law) and the brilliance and intent of our Founders, neither of these have any legal authority over the legal definition of “natural born citizen.” That authority is found in the law alone.

And indeed,

it bears repeating—the Founders themselves vested the authority to

create these laws, and to create legal definitions of terminology, with

Congress. If we are to respect the Framers of the Constitution, that is part of what

we must respect. If we disagree with the current legal definition of

the term, the solution is not to pretend that a different controlling

authority exists, the solution is to challenge the law in court or to

petition our elected representatives to change the law.

And indeed,

it bears repeating—the Founders themselves vested the authority to

create these laws, and to create legal definitions of terminology, with

Congress. If we are to respect the Framers of the Constitution, that is part of what

we must respect. If we disagree with the current legal definition of

the term, the solution is not to pretend that a different controlling

authority exists, the solution is to challenge the law in court or to

petition our elected representatives to change the law.Second, there is no distinction between the terms “natural born citizen” and “citizen at birth.” Legally speaking, both terms mean exactly the same thing. In fact, in the United States, there are only two legally recognized classifications of citizen: Citizen at Birth and Naturalized Citizen. This actually gives us a very easy way to gauge if someone is qualified to serve as President: If they went through a naturalization ceremony to obtain citizenship, they are not so qualified. If, on the other hand, they are a citizen, and never had to be naturalized, as is the case with Senator Cruz, they are eligible. From a legal perspective, it really is that simple.

It can be fascinating looking into the etymology of the phrase natural born citizen, but the historical meanings of a particular phrase are not necessarily the same as, and should not be confused with, its legally defined meaning. The only meaning that carries any legal weight is the one defined in the U.S. Code.

I recognize and respect that passions run high on this subject. But I assure you, you can take this analysis to the bank. And if you are a Ted Cruz fan, then take heart—he really is eligible to run for, and serve as, president!

Update:

Any time I write an article involving presidential eligibility and the Natural Born clause of Article II, a number of standard objections seem to pop up. The claims take a variety of forms, but they usually involve the assertion that when it comes to interpreting and clarifying this particular clause in the Constitution, some other source of authority has primacy over the U.S. Code. There there tends to be a recurring set of objections. I will try to deal with the most common of them here.

1. The Founders said Natural Born Citizen, and the U.S. Code says Citizen at Birth, which mean two completely different things. Therefore the U.S. Code is trumped by the Constitution

Based on United States’ law, the terms Natural Born Citizen and Citizen at Birth are synonymous with each other. Those who claim otherwise need to come up with some authoritative case law clearly distinguishing between the two terms. (Note: The assertion that this is done in Supreme Court cases is dealt with below.) The idea that NBC and CaB are materially different from each other is similar to claiming the words “dog” and “domestic canine” mean different things. They both refer to the same thing: citizenship other than that which comes from naturalization.

In a paper written by the Congressional Research Service, the two terms are explained as well as I have ever seen:

“The weight of legal and historical authority indicates that the term “natural born” citizen would mean a person who is entitled to U.S. citizenship “by birth” or “at birth,” either by being born “in” the United States and under its jurisdiction, even those born to alien parents; by being born abroad to U.S. citizen-parents; or by being born in other situations meeting legal requirements for U.S. citizenship “at birth.” Such term, however, would not include a person who was not a U.S. citizen by birth or at birth, and who was thus born an “alien” required to go through the legal process of “naturalization” to become a U.S. citizen.”Think of it this way: Both terms are meant to distinguish a citizen born subject to the laws, privileges, and responsibilities of a particular state or government from a person who must acquire citizenship through an affirmative act of his own. While there are no writings by the Founders providing a single legal definition of natural born citizen, there are several making clear their intent was to ensure against some individual with loyalties to another king or country from scheming or buying his way into the presidency. Even if someone manages to present evidence of some minutiae distinguishing the separate meanings of NBC and CaB, I have yet to hear anyone explain how it that makes a critical difference in this clearly expressed intent. Which brings us to . . .

2. Title 8 of the U.S. Code carries no weight—the only thing that is important is the intent of the founders, and what they thought “Natural Born Citizen” means.

This is what I refer to as the “Common Law” argument; essentially, it says that the common-law meaning of the term natural born citizen is the only thing that really matters. After all, it is well established that much of the Constitution was undergirded by the Founders’ understanding of English Common law. Unfortunately, the term Natural Born Citizen does not have a fixed, singular meaning, even in the context of common law, but fortunately we do have William Blackstone, who is accepted as a principle authority on the topic.

Blackstone dealt with subjects rather than citizens, as Americans began calling themselves after gaining independence, and Blackstone defined Natural-born Subjects as those “born within the dominions of the crown of England.” Blackstone further held that children of the king’s ambassadors born abroad are always held to be natural subjects. In other words, though such children were born outside English soil, they still retained all the status attached to any other child born within England. Finally, Blackstone also notes that “..more modern statutes these restrictions are still farther taken off: so that all children, born out of the king’s ligeance, whose fathers were natural-born subjects, are now natural-born subjects themselves, to all intents and purposes.” If this sounds familiar, that is because the verbiage of sub-section (d) of section 1401 cited above is based on this same, common-law principle.

Some assert that because this common law principle, as stated by Blackstone and some of the Founders, refers to “fathers,” that Ted Cruz cannot be considered a citizen because it was his mother, not his father, who was the U.S. citizen at the time of his birth. But that is where the U.S. code law enters in. Our laws are informed by common law, but they go on to clarify it for purposes of more precise adjudication of the law. That is why sub-section (d) of section 1401 clarifies the common law version that refers to fathers with a legal version that refers to parents.

3. Case law – I have seen a number of court cases raised as examples which somehow prove some distinct meaning for natural born citizen. Unfortunately, I fear that many (if not most) of the people who cite these cases have not taken the time to actually read them. Here are a few I often see cited, along with a short synopsis of what they really are about:

Minor v. Happersett – This was a suffrage era case that dealt with Missouri’s state law prohibiting women’s voting rights. It obliquely references the 14th Amendment, but says absolutely nothing that could be even remotely construed as a “definition” of “natural born citizen” or how it might be distinct from “citizen at birth.” The principle finding in this case is that citizenship does not confer a right to vote.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark – This case affirms the principle of Jus Soli, or citizenship at birth, established in the 14thAmendment. Most importantly, it established the interpretation of the phrase “..subject to the jurisdiction thereof” as used in that amendment, which principle has remained unchallenged since. The case does not however address or deal with the meaning or definition of natural born citizen beyond this narrow focus, nor does it distinguish that term from citizen at birth.

The Venus – This oddly-named case (Venus was the name of a merchant ship seized by a Privateer, on behalf of the U.S. Government during the War of 1812) from 1814 is actually a property dispute dealing with the disposition of war prizes seized by the United States. The subject of citizenship is tangential at best, and has to do with the government’s arguments over disposition of the property claimed by the plaintiffs. The case does not address citizenship, either natural-born or naturalized, in any way useful to the debate over the meaning of natural born citizen, or any distinction between that and citizen at birth. Its principle significance was in refining the laws of property seizure during war.

Shanks v. DuPont – This case is actually yet another property dispute, and does not deal in any material way with questions about natural born citizenship. In a nutshell, two sisters inherited property in South Carolina upon the death of their father. Both daughters were legally considered citizens by birth, but one married a British officer during the War for Independence and left with him to live out the remainder of her life in England. The dispute was between the children of these two sisters, and was based on the claim that since the British had invaded and occupied parts of South Carolina for a time, including the property in question, this somehow caused the sister who left for England to forfeit her citizenship. The court disagreed.

Perkins v. Elg – This case involved a young girl, born on U.S. soil to Swedish parents (father was naturalized) who returned with her to Sweden a short time after her birth, where they reclaimed their citizenship of that country. The girl returned to the U.S. after her 21st birthday, and her citizenship claim was upheld by the SCOTUS. This case again deals with the principle of Jus Soli, and once again does not address any distinction between natural born citizen and citizen at birth, nor does address any of the claims or controversies about presidential qualifications.

You are certainly welcome to read them for yourselves, but in fact none of these commonly cited cases has any bearing, or even says anything relevant about Article II of the Constitution, nor do they contradict Title 8, Section 1401 of the U.S. Code.

4. but according to Section 1401, Cruz’s mother had to be a government official, or a member of the armed forces in order for him to be a citizen.

This objection is based on subsection (g) of the referenced code, and is based on a misreading of that subsection. What the code is actually saying is, for children born outside the U.S. and its territories, where one parent is a citizen and the other is an alien, (as opposed to a U.S. National, as stated in subsection (d) of the same code) the citizen parent must have been present in the U.S. (or it’s territories) for no less than five years, and any military service or time spent overseas as an employee of the U.S. counts toward that five year requirement. This subsection does not affect Senator Cruz, because his father was still a U.S. National, even though he was not a citizen. And even if it did apply, since his mother had already spent her whole life living within the United States before moving to Calgary, she more than met the requirement, even without having to get credit for time in U.S. service.

Quite often, objections I encounter are based on a misreading of legal language. In other words, the objector is citing code or case law, but (s)he is misinterpreting the meaning of the words. I compliment anyone who is attempting to read the law itself, as the law is the authoritative source for these matters. However, I would ask most earnestly—read it slowly and carefully. Legal language often involves long sentences with multiple clauses. It helps to try to look for the primary subject of each sentence, and the main verb, to get the meaning. Often, it helps to temporarily ignore all the non-restrictive clauses in between.

I’m not a lawyer, and you don’t need to be one in order to understand legal language (though it probably helps). We, the People, can do this. But we have to look to the law as the authoritative source. I guarantee that if this is ever adjudicated in Congress or the courts, that is what they will do.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment