The Mary Bulloch Story and Other Related Issues in the Long Trail of BLM Abuses — by Todd Macfarlane

The recent Hammond Case has stirred a great deal of outrage and disbelief, but it is just the latest drop in the bucket in a long trail of abuses by the Federal Government, Department of Interior, BLM and Forest Service, with respect to their management of public lands in the West, and the people involved. We have talked about some of the issues before, on multiple occasions. But this particular a story, which we have never shared before, seems to paint the overall picture and modus operendi fairly well — especially in situations where the Federal Government wants to remove someone from the land, and take away their property and property rights.

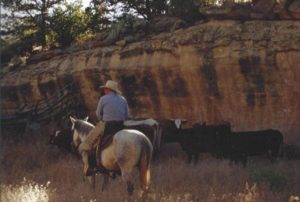

With her husband Boyd Rucker, Mary operated a ranching operation on the Kaiparowits Plateau, in some of the most rugged, remote, and inhospitable country in the lower forty-eight states. The ranch they operated was located entirely on “public land”—land owned by we the people of the United States and “managed” by the Department of the Interior through the BLM.

After Boyd died, following a bad horse wreck on the ranch, it was all Mary could do to operate and maintain the ranch by herself, with a little part-time help from family, friends and neighbors. When the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was created that encompassed the entire ranch, life really changed for Mary—and not for the better. Land that had long been ignored by the BLM now became a focal point, and Mary was subjected to continual harassment by the BLM. Eventually,

it became obvious that the BLM was determined to put her out of business and move her off the land. Although it was suitable for cattle grazing, by any other objective standard the ranch and surrounding area were essentially godforsaken desert, that had little other beneficial use. But under the pretext of drought conditions, the BLM sent Mary a letter stating that all her cattle had to be removed from the ranch by a certain date or be subject to confiscation by the BLM.

Mary had no place else to go. Because of the remoteness, lack of access, and rugged terrain, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to gather her cattle from Fifty Mile Mountain where they grazed in the summertime. Had it been late fall, the cattle would start to come down on their own and could be gathered, but the BLM would not wait until fall. They demanded that all cattle be removed by the end of August. Mary was in a serious bind.

Mary solicited my help. I attempted to reason with the BLM. I also elicited the assistance of Art Tait, a well-respected BLM manager who had always demonstrated a lot of common sense and understanding. Art attempted to work within the agency to mediate a satisfactory resolution, but to no avail. Agency bosses said they were under orders from the top, and were unyielding in their agenda and marching orders. They wanted Mary’s cattle off the range immediately. But Art did manage to secure commitments for a wide range of expensive BLM assistance if Mary would remove her cattle. At the end of the day, Art was so disgusted by the BLM’s attitude, tactics and approach, that ultimately he chose to take early retirement and left the BLM.

Although I considered initiating litigation to seek an injunction, from my perspective what I have often come to describe as the “so-called justice system” was ill-equipped to deal with Mary’s unique situation. Legitimate due process was not even part of the equation. I also knew, from considerable experience, that the thing the justice system is most effective at is consuming resources—resources that Mary Bullock didn’t have. I knew it could consume tens, even hundreds of thousands of dollars, and take years before anything was sorted out. Meanwhile, Mary had no money, and the only way she could get money to live or pay attorneys was from the sale of the cattle she was fighting to save.

While I explored other legal and administrative options, the BLM sought to gather, impound and remove Mary’s cattle. At first the BLM tried to gather the cattle using somewhat traditional means. A crew of BLM bureaucrats and mercenary cowboys attempted to gather cattle in a massive operation that ended in dismal failure. Then the government then spent millions of dollars trying to helicopter-net the cattle, which resulted in only mixed success. When they finally got part of the herd into a corral, the BLM transported the cattle without any regard for state livestock identification and transporation laws. It was their position that because of the Supremacy Clause, as a branch of the federal government, they were exempt from any applicable state laws, including livestock brand, identification, and transportation laws. While Mary’s case languished in the administrative process and legal system, the BLM took the cattle to Producers Auction in Salina, to be sold.

Mary, and a small supporting cast of neighboring ranchers, cowboys and friends showed up at the auction to try to buy the cattle back. They had made signs to inform other ranchers and cattle buyers at the sale what was actually going on. At that point, the BLM canceled the sale and informed Sevier County Sheriff, Phil Barney, that he was responsible for securing, feeding, and caring for the cattle until the BLM could decide what to do. Mary felt helpless. I talked to the Sevier County attorney, Don Brown. Among other things. We discussed the U.S. Supreme Court case Printz & Mack v. The United States. The Printz case is a truly landmark but little known Tenth Amendment case in which the court held that the federal government has no constitutional authority to impart orders to a county sheriff.

At that point, Sheriff Barney decided not to take orders from the BLM. He told Mary he wasn’t taking responsibility for the cattle. “What you do with the cattle is up to you,” the sheriff told Mary, “but we’re not going to be put in the middle of it.”

At that point, Mary secured a brand inspection on the impounded cattle in accordance with applicable state laws. With the cattle identified as hers, Mary and the other ranchers loaded them up to take home. At that point it felt like a victory. They were encouraged.

Early the next morning, their enthusiasm came to an abrupt end when Mary and the wives of other ranchers involved started receiving messages from the U.S. Attorney’s Office threatening federal prison terms and $250,000 fines for “stealing federal property.” The messages detailed a number of other related charges, including aiding, abetting, and conspiracy. The ranchers’ wives, with tears streaming down their faces and panic in their voices, passed the news along to their husbands. It was hard to know what to do. The Feds were driving a hard bargain, and although I didn’t believe they had a legal leg to stand on, that didn’t stop them from making serious threats to coerce the ranchers to roll over and give the cattle back.

When Mary Bullock and her small group of supporting ranchers and friends didn’t immediately cave in, the FBI was at their doorstep with well-practiced intimidation tactics. Still, Mary and her Good Samaritan friends stood their ground, which created a standoff that lasted for weeks. The U.S. Attorney’s Office launched a full media blitz against the ranchers, casting them as vigilante outlaws who had “taken the law into their own hands” and characterizing the sheriff as a rogue with no respect for the rule of law.

Despite the precedent articulated in the Printz case, most of the elected officials in Mary’s own county at the time did little to support her and the other local ranchers. State and local government leaders were largely intimidated by the federal government, and their timid response was, “We’d love to help, but we have to work with these people. We’ve got to go along to get along, and we simply can’t survive around here without federal grants and financial support.”

Mary and her small band of rancher-friends felt like David going against Goliath. It was difficult for the ranchers and their families to weigh the risks and stand their ground. Under threats and ultimatums, fearing the Feds were laying groundwork to justify a more forceful—perhaps even violent—pounce, they waited.

Like a high-noon showdown in an old western movie, the sheriff (local officials) and the townspeople had effectively cleared the street, afraid of the federal bully with the big guns. In this modern-day example, many local leaders were so intimidated by the federal government on one hand and so co-opted on the other hand that they didn’t dare raise their voices in support. Among other things, they feared losing federal grants and program funding they had become dependent upon. In an area dominated by federal public land—land, in fact, that is owned by we the people—local leaders had become so accustomed to going along just to get along that they did not dare say or do anything that might cause them to get crossways with the federal government.

In the end, the federal government did not employ tactics used in places such as Waco, Texas, and Ruby Ridge, Idaho, but the wait was intense because how were Mary and the other ranchers to know how far the government would go? The ranchers and their families could have easily woken up to an army of drawn guns in their faces after their doors had been kicked in at dawn by federal agents.

Sound far-fetched? If you think so, talk to residents of San Juan County, Utah, who were accused of violating federal antiquities laws on public lands.

Enter Agent Dan Love — An Amassed Army of Federal Agents

In the spring of 2009, following a sting operation, in total disregard for local law enforcement and applicable state laws, federal authorities, under the command of BLM Special Agent Dan Love, amassed an army of hundreds of federal agents and dozens of vehicles in a predawn raid, kicking in doors with no-knock warrants and arresting citizens in their beds at gunpoint for nonviolent crimes—citizens who under the U.S. Constitution are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

This was not a drug raid. It had no ties to the War on Terror. There were no violent criminals involved or serious flight risks. Yet, surrounded by swarms of federal agent storm troopers, these people were physically dragged from their homes and hauled away in handcuffs while their children looked on in shock and horror. Over twenty people in the community and surrounding areas were arrested in this manner. As soon as they were able to post bail and be released from custody, two of those arrested (including a prominent and much-loved local doctor) committed suicide rather than continue to be dogged, humiliated and treated this way by the federal government. In the end, not a single one of those arrested that morning received a prison sentence, and the government’s own star witness also committed suicide.

In both this case and the Mary Bullock’ case, it was not the DEA, ICE, INS, IRS, ATF, FBI, CIA or other federal agency normally associated with such brutal tactics that was responsible for these actions. It was the Department of the Interior, the administrative department responsible for oversight of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (and mismanagement of the Native American Trust Fund), Bureau of Reclamation, and Bureau of Land Management. It was in its capacity as a land and resource management agency (BLM)—for we the people—that it engaged in such thuggish and heavy-handed tactics typically thought possible only in totalitarian regimes like the Third Reich or Stalin’s Soviet Union. In both cases, this happened with little, if any, accountability for agency actions. In fact, rather than experiencing any accountability for how the operation was handled, Agent Dan Love was given full charge of “security” for the Bundy operation in Bunkerville in 2014, and true-to-form, was largely responsible for the heavy-handed escalation that occurred there.

To conclude the Mary Bullock story, the federal government ended up spending millions of taxpayer dollars trying to round up the cattle left on Mary’s ranch—cattle that would have left the high country

on their own in a matter of weeks. After warning Mary not to set foot on the ranch again, and after threatening Mary, her attorney, and the ranchers with long prison terms and enormous fines for “stealing government property,” the BLM secretly sent government contractors to the ranch in helicopters to shoot any remaining cattle, leaving them dead for the coyotes and crows to clean up.

Having successfully driven her off the land, without any meaningful accountability whatsoever, the BLM then made it virtually impossible for Mary to sell, or anyone else to successfully operate, what was left of her ranching operation. In the end, Mary Bullock, a once tough-as-nails, free-spirited, freedom-loving American—a one-of-a-kind maverick to be sure—died as a broken and destitute woman at the ripe old age of 55.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://rangefire.us/2016/01/05/the-mary-bullock-story-and-other-related-issues-in-the-long-trail-of-blm-abuses-by-todd-macfarlane/

The Mary Bulloch Story

With her husband Boyd Rucker, Mary operated a ranching operation on the Kaiparowits Plateau, in some of the most rugged, remote, and inhospitable country in the lower forty-eight states. The ranch they operated was located entirely on “public land”—land owned by we the people of the United States and “managed” by the Department of the Interior through the BLM.

After Boyd died, following a bad horse wreck on the ranch, it was all Mary could do to operate and maintain the ranch by herself, with a little part-time help from family, friends and neighbors. When the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was created that encompassed the entire ranch, life really changed for Mary—and not for the better. Land that had long been ignored by the BLM now became a focal point, and Mary was subjected to continual harassment by the BLM. Eventually,

it became obvious that the BLM was determined to put her out of business and move her off the land. Although it was suitable for cattle grazing, by any other objective standard the ranch and surrounding area were essentially godforsaken desert, that had little other beneficial use. But under the pretext of drought conditions, the BLM sent Mary a letter stating that all her cattle had to be removed from the ranch by a certain date or be subject to confiscation by the BLM.

Mary had no place else to go. Because of the remoteness, lack of access, and rugged terrain, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to gather her cattle from Fifty Mile Mountain where they grazed in the summertime. Had it been late fall, the cattle would start to come down on their own and could be gathered, but the BLM would not wait until fall. They demanded that all cattle be removed by the end of August. Mary was in a serious bind.

Mary solicited my help. I attempted to reason with the BLM. I also elicited the assistance of Art Tait, a well-respected BLM manager who had always demonstrated a lot of common sense and understanding. Art attempted to work within the agency to mediate a satisfactory resolution, but to no avail. Agency bosses said they were under orders from the top, and were unyielding in their agenda and marching orders. They wanted Mary’s cattle off the range immediately. But Art did manage to secure commitments for a wide range of expensive BLM assistance if Mary would remove her cattle. At the end of the day, Art was so disgusted by the BLM’s attitude, tactics and approach, that ultimately he chose to take early retirement and left the BLM.

Although I considered initiating litigation to seek an injunction, from my perspective what I have often come to describe as the “so-called justice system” was ill-equipped to deal with Mary’s unique situation. Legitimate due process was not even part of the equation. I also knew, from considerable experience, that the thing the justice system is most effective at is consuming resources—resources that Mary Bullock didn’t have. I knew it could consume tens, even hundreds of thousands of dollars, and take years before anything was sorted out. Meanwhile, Mary had no money, and the only way she could get money to live or pay attorneys was from the sale of the cattle she was fighting to save.

While I explored other legal and administrative options, the BLM sought to gather, impound and remove Mary’s cattle. At first the BLM tried to gather the cattle using somewhat traditional means. A crew of BLM bureaucrats and mercenary cowboys attempted to gather cattle in a massive operation that ended in dismal failure. Then the government then spent millions of dollars trying to helicopter-net the cattle, which resulted in only mixed success. When they finally got part of the herd into a corral, the BLM transported the cattle without any regard for state livestock identification and transporation laws. It was their position that because of the Supremacy Clause, as a branch of the federal government, they were exempt from any applicable state laws, including livestock brand, identification, and transportation laws. While Mary’s case languished in the administrative process and legal system, the BLM took the cattle to Producers Auction in Salina, to be sold.

Mary, and a small supporting cast of neighboring ranchers, cowboys and friends showed up at the auction to try to buy the cattle back. They had made signs to inform other ranchers and cattle buyers at the sale what was actually going on. At that point, the BLM canceled the sale and informed Sevier County Sheriff, Phil Barney, that he was responsible for securing, feeding, and caring for the cattle until the BLM could decide what to do. Mary felt helpless. I talked to the Sevier County attorney, Don Brown. Among other things. We discussed the U.S. Supreme Court case Printz & Mack v. The United States. The Printz case is a truly landmark but little known Tenth Amendment case in which the court held that the federal government has no constitutional authority to impart orders to a county sheriff.

At that point, Sheriff Barney decided not to take orders from the BLM. He told Mary he wasn’t taking responsibility for the cattle. “What you do with the cattle is up to you,” the sheriff told Mary, “but we’re not going to be put in the middle of it.”

At that point, Mary secured a brand inspection on the impounded cattle in accordance with applicable state laws. With the cattle identified as hers, Mary and the other ranchers loaded them up to take home. At that point it felt like a victory. They were encouraged.

Early the next morning, their enthusiasm came to an abrupt end when Mary and the wives of other ranchers involved started receiving messages from the U.S. Attorney’s Office threatening federal prison terms and $250,000 fines for “stealing federal property.” The messages detailed a number of other related charges, including aiding, abetting, and conspiracy. The ranchers’ wives, with tears streaming down their faces and panic in their voices, passed the news along to their husbands. It was hard to know what to do. The Feds were driving a hard bargain, and although I didn’t believe they had a legal leg to stand on, that didn’t stop them from making serious threats to coerce the ranchers to roll over and give the cattle back.

When Mary Bullock and her small group of supporting ranchers and friends didn’t immediately cave in, the FBI was at their doorstep with well-practiced intimidation tactics. Still, Mary and her Good Samaritan friends stood their ground, which created a standoff that lasted for weeks. The U.S. Attorney’s Office launched a full media blitz against the ranchers, casting them as vigilante outlaws who had “taken the law into their own hands” and characterizing the sheriff as a rogue with no respect for the rule of law.

Despite the precedent articulated in the Printz case, most of the elected officials in Mary’s own county at the time did little to support her and the other local ranchers. State and local government leaders were largely intimidated by the federal government, and their timid response was, “We’d love to help, but we have to work with these people. We’ve got to go along to get along, and we simply can’t survive around here without federal grants and financial support.”

Mary and her small band of rancher-friends felt like David going against Goliath. It was difficult for the ranchers and their families to weigh the risks and stand their ground. Under threats and ultimatums, fearing the Feds were laying groundwork to justify a more forceful—perhaps even violent—pounce, they waited.

Like a high-noon showdown in an old western movie, the sheriff (local officials) and the townspeople had effectively cleared the street, afraid of the federal bully with the big guns. In this modern-day example, many local leaders were so intimidated by the federal government on one hand and so co-opted on the other hand that they didn’t dare raise their voices in support. Among other things, they feared losing federal grants and program funding they had become dependent upon. In an area dominated by federal public land—land, in fact, that is owned by we the people—local leaders had become so accustomed to going along just to get along that they did not dare say or do anything that might cause them to get crossways with the federal government.

In the end, the federal government did not employ tactics used in places such as Waco, Texas, and Ruby Ridge, Idaho, but the wait was intense because how were Mary and the other ranchers to know how far the government would go? The ranchers and their families could have easily woken up to an army of drawn guns in their faces after their doors had been kicked in at dawn by federal agents.

Sound far-fetched? If you think so, talk to residents of San Juan County, Utah, who were accused of violating federal antiquities laws on public lands.

Enter Agent Dan Love — An Amassed Army of Federal Agents

In the spring of 2009, following a sting operation, in total disregard for local law enforcement and applicable state laws, federal authorities, under the command of BLM Special Agent Dan Love, amassed an army of hundreds of federal agents and dozens of vehicles in a predawn raid, kicking in doors with no-knock warrants and arresting citizens in their beds at gunpoint for nonviolent crimes—citizens who under the U.S. Constitution are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

This was not a drug raid. It had no ties to the War on Terror. There were no violent criminals involved or serious flight risks. Yet, surrounded by swarms of federal agent storm troopers, these people were physically dragged from their homes and hauled away in handcuffs while their children looked on in shock and horror. Over twenty people in the community and surrounding areas were arrested in this manner. As soon as they were able to post bail and be released from custody, two of those arrested (including a prominent and much-loved local doctor) committed suicide rather than continue to be dogged, humiliated and treated this way by the federal government. In the end, not a single one of those arrested that morning received a prison sentence, and the government’s own star witness also committed suicide.

In both this case and the Mary Bullock’ case, it was not the DEA, ICE, INS, IRS, ATF, FBI, CIA or other federal agency normally associated with such brutal tactics that was responsible for these actions. It was the Department of the Interior, the administrative department responsible for oversight of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (and mismanagement of the Native American Trust Fund), Bureau of Reclamation, and Bureau of Land Management. It was in its capacity as a land and resource management agency (BLM)—for we the people—that it engaged in such thuggish and heavy-handed tactics typically thought possible only in totalitarian regimes like the Third Reich or Stalin’s Soviet Union. In both cases, this happened with little, if any, accountability for agency actions. In fact, rather than experiencing any accountability for how the operation was handled, Agent Dan Love was given full charge of “security” for the Bundy operation in Bunkerville in 2014, and true-to-form, was largely responsible for the heavy-handed escalation that occurred there.

To conclude the Mary Bullock story, the federal government ended up spending millions of taxpayer dollars trying to round up the cattle left on Mary’s ranch—cattle that would have left the high country

on their own in a matter of weeks. After warning Mary not to set foot on the ranch again, and after threatening Mary, her attorney, and the ranchers with long prison terms and enormous fines for “stealing government property,” the BLM secretly sent government contractors to the ranch in helicopters to shoot any remaining cattle, leaving them dead for the coyotes and crows to clean up.

Having successfully driven her off the land, without any meaningful accountability whatsoever, the BLM then made it virtually impossible for Mary to sell, or anyone else to successfully operate, what was left of her ranching operation. In the end, Mary Bullock, a once tough-as-nails, free-spirited, freedom-loving American—a one-of-a-kind maverick to be sure—died as a broken and destitute woman at the ripe old age of 55.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://rangefire.us/2016/01/05/the-mary-bullock-story-and-other-related-issues-in-the-long-trail-of-blm-abuses-by-todd-macfarlane/

Mary solicited my help. I attempted to reason with the BLM. I also elicited the assistance of Art Tait, a well-respected BLM manager who had always demonstrated a lot of common sense and understanding. Art attempted to work within the agency to mediate a satisfactory resolution, but to no avail. Agency bosses said they were under orders from the top, and were unyielding in their agenda and marching orders. They wanted Mary’s cattle off the range immediately. But Art did manage to secure commitments for a wide range of expensive BLM assistance if Mary would remove her cattle. At the end of the day, Art was so disgusted by the BLM’s attitude, tactics and approach, that ultimately he chose to take early retirement and left the BLM.

Mary solicited my help. I attempted to reason with the BLM. I also elicited the assistance of Art Tait, a well-respected BLM manager who had always demonstrated a lot of common sense and understanding. Art attempted to work within the agency to mediate a satisfactory resolution, but to no avail. Agency bosses said they were under orders from the top, and were unyielding in their agenda and marching orders. They wanted Mary’s cattle off the range immediately. But Art did manage to secure commitments for a wide range of expensive BLM assistance if Mary would remove her cattle. At the end of the day, Art was so disgusted by the BLM’s attitude, tactics and approach, that ultimately he chose to take early retirement and left the BLM. While I explored other legal and administrative options, the BLM sought to gather, impound and remove Mary’s cattle. At first the BLM tried to gather the cattle using somewhat traditional means. A crew of BLM bureaucrats and mercenary cowboys attempted to gather cattle in a massive operation that ended in dismal failure. Then the government then spent millions of dollars trying to helicopter-net the cattle, which resulted in only mixed success. When they finally got part of the herd into a corral, the BLM transported the cattle without any regard for state livestock identification and transporation laws. It was their position that because of the Supremacy Clause, as a branch of the federal government, they were exempt from any applicable state laws, including livestock brand, identification, and transportation laws. While Mary’s case languished in the administrative process and legal system, the BLM took the cattle to Producers Auction in Salina, to be sold.

While I explored other legal and administrative options, the BLM sought to gather, impound and remove Mary’s cattle. At first the BLM tried to gather the cattle using somewhat traditional means. A crew of BLM bureaucrats and mercenary cowboys attempted to gather cattle in a massive operation that ended in dismal failure. Then the government then spent millions of dollars trying to helicopter-net the cattle, which resulted in only mixed success. When they finally got part of the herd into a corral, the BLM transported the cattle without any regard for state livestock identification and transporation laws. It was their position that because of the Supremacy Clause, as a branch of the federal government, they were exempt from any applicable state laws, including livestock brand, identification, and transportation laws. While Mary’s case languished in the administrative process and legal system, the BLM took the cattle to Producers Auction in Salina, to be sold. Enter Agent Dan Love — An Amassed Army of Federal Agents

Enter Agent Dan Love — An Amassed Army of Federal Agents

No comments:

Post a Comment