The ranchers were following in the footsteps of Arizona rancher LaVoy Finicum, who at the time was a leader of a land-use protest at an Oregon wildlife refuge and who had publicly refused to pay for grazing rights.

Then on 26 January, state troopers in Oregon shot and killed Finicum during an attempted arrest, and two weeks after that, federal authorities detained and charged Cliven Bundy, the Nevada rancher who led an armed standoff at his property in 2014.

But in remote desert ranges of Utah, ranchers say they remain committed to finding a way to stand up to what they see as federal overreach and mistreatment – even if the most vocal activists leading the charge are now dead or behind bars.

There are a number of factors that make Utah a key battleground in the brewing fight, with some questioning whether tensions could boil over and erupt in the form of another high-profile standoff and national controversy.

Some in rural parts of central and southern Utah tell stories of extreme overreach by the government, alleging that the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and environmental advocacy groups have used endangered species regulations and conservation initiatives to prevent families from sustaining ranches passed down through generations.

Environmentalists, meanwhile, argue that the federal government, which controls roughly 66% of the land in Utah, plays a vital role in protecting habitats and regulating multiple land uses – and that if ranchers had more discretion to graze, the consequences would be devastating.

Utah ranchers who support the Finicums and the Bundys say they want to avoid the dramatic conflicts that emerged in Oregon and Nevada, which resulted in mass arrests of anti-government activists. But they also say they feel like they are running out of options in the face of grazing restrictions that they claim have been so harmful they’ve considered altogether disavowing their government contracts.

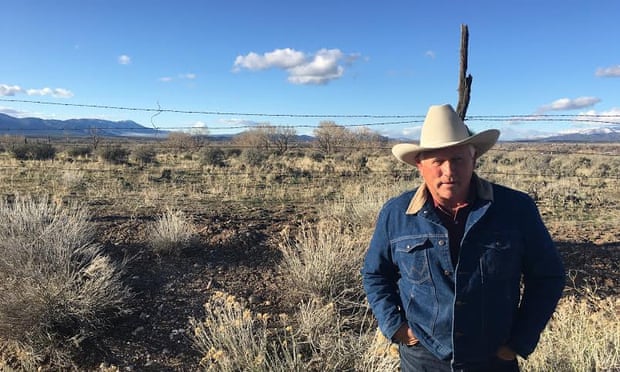

“Utah needs to stand up and take their land back,” said Stanton Gleave, a 66-year-old Kingston rancher and one of the men who signed a “withdrawal of consent” document in January. “I don’t think we was ever supposed to be governed by a federal government. We’re supposed to be a free people … If we was ever free, we’ve lost it somewhere down the line.”

Gleave and other ranchers who had declared their intent to reject federal grazing agreements decided not to follow through with that threat. But they say they are anxious to see some kind of major legislative shift that would remove the BLM from Utah’s public lands – a long shot even in the conservative Beehive State, where many lawmakers and state officials are sympathetic to the ranchers and deeply critical of the federal government.

It’s not hard to find links between the Utah ranching community and the recent Oregon standoff at the Malheur national wildlife refuge, which lasted 41 days and was inspired by the prosecution and imprisonment of two ranchers in a federal arson case.

Finicum, a key spokesman for the Oregon occupation, had traveled to Utah before and during the standoff to recruit ranchers to renounce the BLM, and at his funeral in his hometown of Kanab supporters from across the west hailed him as a patriot who died fighting for ranchers’ rights.

On a recent evening, Gleave and three other ranchers gathered at a diner in Beaver, a tiny rural town in southern Utah, along Interstate 15, to share their stories of how they’ve fought with the BLM – and their fears that the government wants to eventually push them off their land altogether.

From 1949 to 2012, grazing on BLM land in Utah declined by 68% and the number of families ranching on federal rangelands dropped by 58%, according to AUM data provided by Randy Parker, chief executive officer of the Utah farm bureau.

“These are people that were ranching and grazing on land held in common in Utah before there was ever a public domain,” Parker said. “These ranching businesses are absolutely critical to the economic, cultural and historical health of these rural cities and towns.”

Utah Republicans have pursued numerous legislative and legal avenues to establish state control of public lands – most recently preparing for a potential lawsuit against the federal government.

State representatives and county commissioners say they want to limit the federal government’s power and find legal ways to mitigate the growing anger of ranchers – so that they don’t escalate in the form of a standoff.

“We strongly adhere to the rule of law,” said state representative Keven Stratton, who has backed efforts to establish state control of federal land. “I have sympathy for the frustration, but there are appropriate ways to deal with that and inappropriate ways.”

Shelley Smith, deputy state director for the BLM in Utah, said that the agency works with ranchers to address their grievances. “Most of the time we’re in pretty harmonious working relationships with our ranchers.”

Asked about threats by ranchers to ignore contracts, Smith said: “We’re concerned when people feel they haven’t been heard.” But she noted that all 1,478 BLM ranching permits in the state have been paid and also argued that a small fraction of ranchers have formally appealed BLM’s permit decisions over the past 20 years.

Smith added: “We manage these lands on behalf of all Americans for the stewardship of a couple dozen resources. We are always trying to find that Rubik’s Cube puzzle match. Most of the time we do a pretty good job.”

Bill Hedden, executive director of the Grand Canyon Trust, a Utah environmental group, said the complaints of ranchers were wildly exaggerated – and that BLM’s restrictions are critical to the health of the land. “America has decided they are public lands,” he said. “No matter how these guys want to rewrite history … these never were their lands.”

No comments:

Post a Comment